Ethnic Inclinations in Sudan’s RSF Militia: (2–3) The Future Impact on Neighbouring States from Where RSF Recruits

Sudanhorizon: Mohamed Othman Adam

Researcher Yasir Zidan writes, in the study we are reviewing in these instalments:

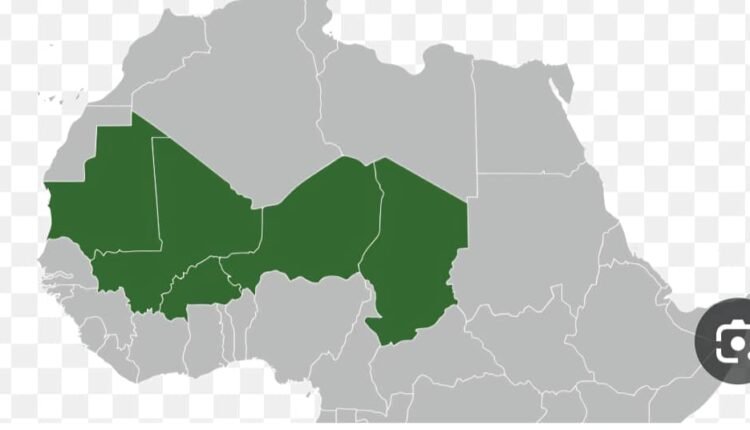

One of the most important strategic shifts in the RSF’s operations lay in recruitment. While recruitment remained rooted among Arab tribes in Darfur, the RSF began recruiting from across the Sahel—especially from Chad, Niger and Libya—leveraging kinship ties, long-standing trading links, and the region’s military labour economies.

Fighters were drawn to the RSF by economic desperation, ideological affinity, or kin-based obligations, expanding its operations beyond Sudan’s borders. In this sense, the RSF is no longer merely a national force but a regional actor—capable of influencing conflicts across a wider Sahelian zone.

This trajectory—from a tribal militia to a quasi-private, transnational armed enterprise—shows how the RSF has become a hybrid institution operating across sovereign borders. The RSF now exemplifies what may be termed “substitute governance”: de facto rule in areas where state authority is weak or absent.

In many parts of Sudan and neighbouring countries, the RSF has replaced or captured traditional authorities, using informal taxation, resource control, and coercive policing to entrench local dominance. Its operations blur the lines between public and private security, state and non-state violence.

As European writers Alex de Waal and Jérôme Tubiana have noted, the Janjaweed and their allies have always formed an integral part of local political economies. These militias existed in a grey zone between state violence and tribal autonomy, and the RSF inherited that ambiguity. By embedding itself in both state institutions and tribal structures, the RSF has maintained a dual legitimacy that complicates efforts at disarmament or demobilisation. Roessler’s theory of the coup–civil war trap is particularly apposite here: Hemedti’s rise illustrates how elite fragmentation and the militarisation of ethnic circles are used to hedge against regime collapse. The RSF’s structure ensures that any threat to Hemedti is met by mobilising loyal fighters whose interests are tied to his survival.

Tension with the Sudanese Armed Forces after 2019

The RSF and the army signed a transitional agreement, but this did not prevent escalating disputes over the timeline for integrating the RSF into the army. The SAF proposed integration within two years, while Hemedti sought ten. The deadlock culminated in force build-ups around Khartoum. In a provocative move, the RSF encircled the Merowe airbase in northern Sudan, igniting full-scale conflict. What began as a bureaucratic contest over command and control morphed into a national confrontation with grave consequences.

By then, the RSF had cultivated external alliances—maintaining ties with General Haftar in Libya and cooperating with Russia’s Wagner Group. These links insulated the RSF from domestic constraints and emboldened its actions. With foreign patrons and independent revenue streams, the RSF became less responsive to Sudanese state oversight. Regional relationships facilitated flows of weapons, personnel and intelligence, bolstering its status as a sovereign-like actor within and beyond Sudan.

In short, the RSF’s origins reflect wider patterns in African armed politics: the privatisation of violence, the blurring of military and commercial interests, and the hollowing-out of state sovereignty. It has become emblematic of a post-sovereign security order, where legitimacy stems not from legal mandates but from force, finance and flexible loyalties.

The RSF’s transformation—from tribal militia to institutionalised armed actor—illustrates the convergence of security governance and war economies in fragile states.

Understanding this evolution is essential to grasping the current Sudan crisis and the cross-border threats posed by ethnically recruited mercenary formations. Future peacebuilding must account for these hybrid forces, not just as spoilers or auxiliaries, but as pivotal actors in reshaping political authority in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa.

Arab Tribal Networks and Cross-Border Mobilisation in the Sahel

The recruitment of fighters from Chad, Niger and Libya relies on established kinship structures and nomadic migration patterns that pre-date modern state boundaries. Arab tribes—especially the Baggāra and Abbala—have long practised mobility, herding, trade and intermarriage over vast distances, weaving a dense web of social relations resilient to the disintegration of regional sovereignties.

The RSF’s current cross-border recruitment cannot be understood without acknowledging the deep historical presence of Arab tribes and their capacity for mobility across the Sahel.

Historically, Arab migrations into Africa began as early as the seventh century, following the expansion of Islam. Trade and pilgrimage routes carried Arabs from the Hijaz to far-flung places such as the Fulani Sultanate in West Africa.

Libya saw multiple waves of Arab settlement during the Berber sultanates. Over time, Arabs moved into Chad and Sudan through forced displacement and economic opportunity, establishing a lasting presence in Wadai (eastern Chad) and in Darfur—creating what scholars describe as an Arab belt stretching from Sudan to Niger.

British anthropologist E. E. Evans-Pritchard captured the nomadic spirit when he quoted a man of the Awlād ‘Alī: “We do not consider any place our homeland. Our homeland is where there is grass and water.”

These communities have gone by various names, including Arab Shuwa in Niger, where they settled and intermarried with local populations. In Sudan, Arabisation intensified given the region’s position as a bridge between the Arab world and Sub-Saharan Africa. Though far from homogeneous, these Arab communities share overlapping cultural and linguistic affinities that still matter in today’s geopolitics. This history of migration and adaptation underpins the RSF’s present strategy of leveraging Arab kinship networks for manpower and legitimacy.

Those tribal bonds are now mobilised for war. The RSF has exploited transnational Arab identities to widen its recruitment base beyond Sudan. In areas where the state is weak or absent, Arab tribal groupings often function as de facto authorities, providing social cohesion and local governance. These affiliations are not mere cultural continuities—they are operational assets. During the current conflict, videos and social media posts have shown fighters from Chad and Niger aligning with Hemedti and the RSF, often framing their participation in religious and ethnic terms. This mobilisation is neither spontaneous nor purely ideological: it is part of a broader military economy in which ethnicity serves as a logic of recruitment and a currency of trust.

This dynamic reflects a politics of negotiation characteristic of governance in unregulated spaces. In such contexts, allegiances and authority are fluid, bargained between local actors, militias and state forces. Tribal identity becomes a form of currency, easing the movement of fighters, weapons and supplies across porous borders.

Arab identity, in this case, legitimises the presence of foreign fighters in Sudan and frames their involvement as part of a moral, historical struggle. The RSF also offers tangible incentives: in areas beset by youth unemployment, state neglect and chronic insecurity, violence becomes practical work. The RSF provides pay, arms and opportunities for looting, creating an informal military labour market open to fighters across the Sahel.

A camp-based patronage system undergirds this—reinforced by regional alliances, access to gold mines, and foreign backing from Gulf states to Russia’s Wagner Group.

The normalisation of cross-border Arab militia participation in Sudan signals a shift in how conflict is organised and fought in the Sahel. It challenges conventional concepts of national armies and rebel groups by highlighting the hybrid nature of actors like the RSF, who operate across ethnic, economic, political and regional registers.

These militias are not merely local phenomena; they are embedded in transnational matrices of relations shaped by centuries of movement, trade and shared struggle. This understanding invites a reframing of Sahelian militias—not as irregular aberrations, but as political actors rooted in established social systems.

The RSF’s strategic use of Arab tribal networks shows how identity and mobility can be exploited to sustain cross-border violence. It also raises pressing questions about the future of governance in the region, where non-state armed groups increasingly exercise de facto authority and redefine the contours of political belonging.

Climate Change, Land Conflict, and the Erosion of Tribal Authority in the Sahel

Environmental degradation in the Sahel has profoundly reshaped the region’s social and political landscape—especially among Arab nomadic groups. Severe droughts in the 1970s and 1980s marked a turning point in pastoral livelihoods. As rainfall declined and desertification accelerated, nomads—who defined “home” as wherever grass and water existed—faced the collapse of grazing corridors, displacement from ancestral lands, and intensifying competition with settled farming communities. This environmental crisis—exacerbated by weak land-tenure systems and ethnically biased governance—spurred a broader transformation in tribal authority and conflict dynamics.

Historically, Arab pastoralists in the Sahel—particularly the Abbala and Baggāra—relied on seasonal mobility across semi-arid rangelands. Their movement was governed by customary regimes and traditional mediation led by tribal sheikhs.

In Darfur, the hakūra land-tenure system, originating under the pre-colonial Fur Sultanate, granted collective land rights tied to tribal affiliation and administrative responsibilities.

Colonial and post-colonial administrations weakened these arrangements. British indirect rule co-opted tribal leadership and codified inequality of land access. The hakūra, originally a fiscal structure for taxation, was redefined through a tribal lens as land rights grew more politicised.

Southern Baggāra tribes—Rizeigat, Ta‘aisha, Habbaniyya—long recognised their tribal homelands (dār) and were integrated into the hakūra system. By contrast, northern Abbala—such as the Mahāmīd and Mahariyya—remained landless and highly mobile, often grazing in zones formally allocated to others. The absence of formal rights produced recurrent frictions with settled communities and the political marginalisation of the Abbala. As population pressures grew and arable land shrank, inter-tribal tensions escalated into violence.

The severe droughts of 1983–84 triggered mass displacement, notably from northern Darfur and Chad into Sudan’s central agricultural belt. These migrations strained local resources and institutions, sparking herder–farmer clashes over access to cultivable land.

As resource disputes intensified, traditional mediation mechanisms weakened. The authority of tribal elders—once guarantors of peace through practices like blood-compensation (diyya)—came under growing challenge. The widespread diffusion of small arms further eroded these institutions.

State interventions often worsened matters: instead of reinforcing customary authorities, governments bypassed them, favouring armed youth who promised political loyalty and battlefield utility. Militarisation intensified under Sadiq al-Mahdi and Omar al-Bashir, who exploited land grievances for political ends.

The decision to arm landless Arab tribes in Darfur in the early 2000s transformed environmental displacement into militarised identity politics. The Janjaweed militias—later evolving into the RSF—drew heavily from these dispossessed communities.

The RSF emerged as a new kind of tribal authority—rooted not in customary legitimacy but in coercion and financial incentives. By offering mercenary wages, control over loot, and access to land and gold, the RSF attracted large numbers of disaffected youth. This patronage structure effectively redefined tribal leadership on militarised terms, severing the historic link between tribal authority and community stability, and replacing it with external alliances and commodified violence. In effect, the RSF exploits these conditions through two interlinked tactics that outline four pillars of ethnic mercenarism:

Identity-linked recruitment, akin to Sudan’s historic quasi-military labour market—visible in current RSF practices.

Material incentive: institutionalised looting and access to gold sites as compensation, formalising the logic of “violence as work” while keeping fixed payroll costs down as war persists.

Both strategies exploit climate deterioration, which has generated a larger supply of recruitable pastoral youth. Together they convert structural shocks—expanded armed-labour supply and weakened mediation—into paid, identity-driven mobilisation across borders: ethnic mercenarism in practice.

Climate change remains the backdrop to this militarisation. As rainfall continues to decline and arable land contracts, competition over natural resources in Darfur and beyond intensifies.

The overlap of environmental crisis, state manipulation, and weak tribal governance has created fertile ground for ethnic mercenarism. Conflicts that begin as disputes over water and grazing routes escalate rapidly into ethnic violence when layered with historical grievances and military patronage.

From 1998 onwards, intermittent land clashes became more lethal. Human Rights Watch reported that conflicts between Masalit farmers and Arab herders in West Darfur forced thousands to flee and resulted in the killing of numerous tribal leaders.

Government responses prioritised security over reconciliation, further undermining local intermediaries. These dynamics show how land scarcity, placed within a militarised setting, turns pastoral grievances into strategic violence.

Across the arid zones of the Sahel and Sudan, rising temperatures, erratic rainfall and land degradation have undermined the livelihoods of farmers and herders alike, expanding the cohort of youth for whom paid fighting becomes a viable occupation.

The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report identifies pastoralists as highly vulnerable to climate shocks, while UNEP’s assessment for Sudan links desertification and land degradation to worsening resource conflicts in Darfur. The same structural conditions—climate fragility, weak governance, ethnic stratification—have driven similar dynamics in Niger, Mali and Chad.

Understanding how environmental pressures and failed land reform trigger military responses is key to explaining not only the RSF’s rise, but also the broader transformation of conflict across the region.

In sum, the erosion of tribal authority in the Sahel is both cause and consequence of environmental collapse and militarised governance. The RSF is not an aberration but a symptom of deeper structural shifts—where violence has become an organising principle of power, and historic systems of mediation and land management have given way to armed patronage networks. As climate change continues to reshape the region’s natural and political environment, these hybrid formations are likely to remain central to its future.

(Part 3, the final batch in the series, to follow.)

Shortlink: https://sudanhorizon.com/?p=8293