Men like Hajj Abbas Among the People!

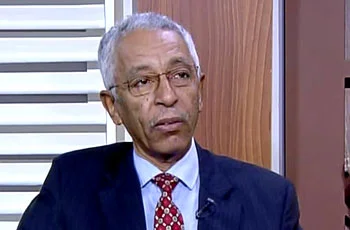

Dr Al-Khidir Haroun

He said: I was an administrative officer, moving between towns of Sudan – north, south and west – until my journey ended in the town of Aroma in eastern Sudan. Today, it is a completely forgotten place, its very state telling stories of how towns die. It was once the centre of the Gash Agricultural Project, with a cardboard factory, and it was on the ring railway line from Khartoum through Sennar, Gedaref and Kassala to Port Sudan, which we left unnamed and called Port Sudan! I do not know why, when it was made a substitute for the historic Red Sea bride, Suakin, they did not call it “New Suakin” or even “Sinkat” after the nearby town just an hour’s drive to the south – which, I often wondered, why was it never made a summer resort, adorned with wide streets and elegant buildings, especially as it enjoys a temperate climate!

I said to myself, why be surprised? Sudan, vast as it is, has been described but not truly named – its people dark and not-so-dark in complexion, the land of the blacks! Had we kept our old name, Ethiopia, before Haile Selassie claimed it, we would not have escaped description either – “the land of scorched faces”! What a pity!

My grandmother once said, after a long explanation: “Mukhair Allah, what kind of calamity is this? Was there ever a shortage of names?” She said that when she performed the pilgrimage in the 1930s, the people of Jeddah welcomed them with the greeting: “Welcome, Sananiir!” – meaning the people of the Sennar kingdom.

From my journeys across Sudan, I gained above all a love for its places and people – in Sennar and Dilling, in Wau, Merowe and Shendi. And in Aroma, there was Hajj Abbas – a tall, light-brown-skinned man, always neat and well turned out, though around sixty years of age. He wore a spotless white jallabiya with either a turban or a skullcap on his head, a short rounded beard and a light moustache, and his clothes carried the scent of Rivdor perfume. You would think him a man of the East, but he told me he was from the area of Al-Zaidab in the Northern State, raised and educated in Shendi. Hajj Abbas owned a small shop, and he led us in prayer at a nearby zawiya for the five daily prayers.

We shared the experience of moving from town to town across Sudan. He told me he had left school after his second year of secondary because his mathematics teacher made a habit of humiliating him. His father, an educated man keen on his son’s education, offered to transfer him to another school, but could not persuade him. Instead, he found him a small clerical job in the Sudan Railways, and so Abbas moved, as I did, from station to station until he retired by choice.

This gave us an endless supply of conversation, so many experiences in common. I would pass by before sunset and we would sit, chatting into the evening over cups of tea and eastern coffee flavoured with ginger. I said to him once: “They say you married eleven times.” He smiled knowingly, as though no answer in the world would suffice to convince, and said: “And what of it? I committed no crime, no sin. I never kept in my household more than the law of God allowed. My uncle married seventeen times – as you see, I have not yet reached a quorum!” Then he laughed.

I asked: “Do you still have the energy for it?” He replied: “Yes, but I have stopped now. I am like that man of Baghdad who left children of every type and kind in every city he passed through – except a doctor, who could have cured me of these rheumatic pains.” I said: “But you do have managers, professors, schoolteachers, and even an internationally known artist among your children.” He was delighted with my correction, as many people are when you lift their spirits. “Indeed,” he said, “they have not failed me. They took me to pilgrimage many times, and built me this spacious house and this shop.”

I asked: “But why here?” He said: “Because I wished it so. I have sons and daughters from most of the towns where I worked – about twenty in all. But my last wife was from this town, the most beautiful of them all. May God have mercy on her, she died and left me one daughter who was deeply attached to me. Though she is under the care of a noble husband and has children of her own who are attached to me too, she has no brother or sister here. So I chose to spend the rest of my days by her side.”

Often, customers would come and go while he remained seated by my side. A shy young woman would stand at a distance and say: “Uncle Hajj Abbas, I want a few tins of tomato paste.” He would answer: “Go inside, you’ll find them on the top shelf. Leave the money in the drawer. If you don’t have it, write it in the account book, or remind me another day.” Then a boy or girl would come: “Uncle Hajj, my father says we need a box of matches, two pounds of tea and a bottle of oil.” He would reply, calling the child by name: “You are a clever one – you know how to weigh, and you know where the things are. Take what you need and write it in the book.”

I was astonished. “How do you run your shop like this, trusting everyone?” He smiled and said: “These people have become like my family. I know their honesty, and they have never disappointed me. They write down exactly what they take. A few cannot repay, but I never press them. By God’s grace, we get by, as you see.” I knew he was embellishing things a little, for he lived modestly and only just got by. Some of his children were wealthy and urged him to join them in the big cities, but he chose to stay in Aroma with his daughter.

I asked him: “Tell me, why were you such a marrying man?” He laughed: “I told you, I entered the service young, in the bloom of youth and strength. My colleagues in the staff quarters went to the brothels – legal at the time – but my grandfather, a pious Qur’an teacher, once made me swear never to commit fornication. My father, a lightly religious civil servant, would protest every time I married. I married in Wau, in Babanoosa, in many other places. He never attended any of my weddings – except the last, here in Aroma. My wife here was like the twin of the legendary Tajouj, beloved of Wad Muhalliq. The old man, may God rest him, wished he still had the vigour to do as I did with the beauties of this town, which, they say, was named after its wild, fragrant flowers.” He laughed again.

Sometimes he would take me to a café in the town market, where people gathered around him in welcome, and those with needs approached him, while he sat there happy and smiling.

When the time came for my transfer to another town, we both avoided looking into each other’s eyes. But he held me tight, and I felt his tears falling on my chest.

One draws love of the homeland from men like Hajj Abbas. You find them in every town, living happily and contentedly among ordinary people, like shining moons. They bind up wounds, wipe away tears and sorrows, with little, with resourcefulness, with nothing at all but consolation and kind words. May God bless them!

Shortlink: https://sudanhorizon.com/?p=7124