Ethnic Inclinations in Sudan’s RSF Militia and the Sahelian Arab Belt in Africa (1–3)

Sudanhorizon – Mohamed Othman Adam

A comprehensive, in-depth study by researcher Yasir Zidan examines a phenomenon he terms “ethnic mercenarism”—a label closely tied, in both form and substance, to the composition and behaviour of Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia and to rebel groups in Sub-Saharan states. Recruitment occurs within an ethnic/tribal frame—narrower even than mercenarism—driven by tribal allegiance and ethnic solidarity, as well as material gain. It differs from paid, contractual mercenarism that ends with the mission; here it spills over into looting, killing, ethnic revenge and score-settling that continue even after an area is seized.

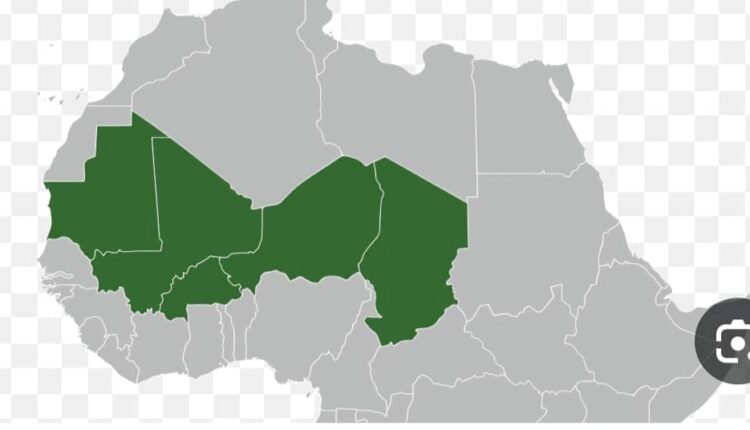

The researcher argues that the ongoing war in Sudan has revealed this new phenomenon: individuals from Arab tribes along the “Arab Baggāra Belt” in Chad, Libya and Niger have joined the RSF in its war against the Sudanese Armed Forces. The report, therefore, probes the root causes of this new mercenary dynamic emerging in Sudan and whether ethnic networks have facilitated recruitment.

He notes that the use of mercenary forces has a long history in Africa and that, recently, mercenaries have gained influence as governments across the continent tacitly acknowledge their armies’ inability to contain the growing power of armed groups. What is striking, however, is that current studies largely frame cross-border militia recruitment as “terrorism”, while overlooking the new, rising formation of ethnic mercenarism in the Sahel.

The study contends that cross-border recruitment of Arab militias cannot be fully explained through counter-terrorism, migration or ideology alone; rather, it reflects the militarisation of Arab pastoral communities amid state collapse, mounting environmental pressures, and cross-border opportunity structures.

The RSF is situated within broader patterns of war economies and tribal governance in the Sahel. The study underscores the need for a new framework to understand irregular militias that transcend national borders, formal ideologies and classic insurgency models. While contemporary literature tends to subsume cross-border militia recruitment under terrorism, it has not adequately examined ethnicity-based recruitment in Sudan and the Sahel. This emerging phenomenon challenges national borders across the region and threatens regional and international security.

Some analysts have attributed ethnicity-based recruitment to an ideology of Arab dominance/supremacy. This research, by contrast, argues that multiple factors contributed to the RSF’s recruitment of non-Sudanese Arab fighters in the current war.

What is beyond dispute is that Arab-supremacist ideology, land disputes, desertification, and local/regional interventions have all helped produce the phenomenon of ethnic mercenarism in the Sahel.

The researcher adds that the complex factors that generate ethnically based mercenaries in Sudan, Chad, and Niger call for a nuanced approach—one that goes beyond (post)colonial explanations to include the contemporary social and security dynamics that shape conditions in the Sahel.

Tracing the many root causes behind inter-state ethnic militias leads to an alternative theory: states’ preoccupation with asserting sovereignty has helped create ungoverned spaces in countries like Sudan and Chad. Government policies to arm select segments of ethnic groups have further weakened traditional tribal authorities that had prevailed in these areas for decades.

Academic studies have shed some light on state-linked militias and inter-state terrorist networks in the Sahel. Much less has been done to explore contemporary ethnic linkages among Arab militias. These tribal bonds came to the fore during Sudan’s current war, as militias used fighters from neighbouring countries in their operations—a pattern echoed in the civil wars in Libya, Chad and Niger. This marks a notable re-emergence of older social dynamics in Sub-Saharan Africa:

The dynamics we see in these conflicts are rooted in Arab migrations caused by drought and forced displacement since the fourteenth century.

The study calls for greater focus on how identity, survival, and foreign sponsorship intersect to produce a distinct Sahelian pattern of mercenarism—one that challenges assumptions about state control, loyalty, and the organisation of violence in contemporary African wars.

Sources and Method

The study draws on field observations and primary material collected during the first weeks of the 2023 Sudan conflict. The author was in Khartoum when clashes first erupted between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the RSF in April 2023. During this period, he held informal conversations with civilians, humanitarian workers, and individuals closely connected to RSF fighters—providing first-hand perspectives on the group’s mobilisation and conduct. He also conducted remote, semi-structured interviews with community leaders and conflict-affected residents identified through purposive and snowball sampling.

Additional insights were derived from systematic monitoring of social media platforms, including Telegram and Facebook, where RSF-related content and testimonies proliferated. These digital sources were cross-referenced with reports from international news agencies and prior academic studies.

The study employed basic open-source verification: establishing the origin of sources, uploader identities, publication dates, ethnic ties and possible political affiliations, then geolocating images and videos by matching terrain, buildings and distinctive landmarks. It acknowledges the biases and limits of social-media evidence and interviews, and thus leverages the author’s long-term engagement with Red Sea and Sahel politics, including prior fieldwork in East Africa. Despite wartime travel restrictions and the informality of sources, the approach prioritises empirical grounding and situational proximity, integrating qualitative evidence with secondary sources to reconstruct the social-political dynamics underpinning the RSF’s cross-border recruitment practices.

Conceptualising “Ethnic Mercenarism”

The study argues that the ethnic mercenarism and shifting nature of armed groups—together with the RSF’s emergence as a transnational force—require rethinking established frameworks for studying armed actors. Traditional labels—rebels, terrorists, warlords—do not fully capture hybrids like the RSF.

Here, “ethnic mercenarism” is defined as a mode of armed mobilisation in which recruitment and cohesion are channelled primarily through transnational ethnic-tribal networks; material incentives (wages, spoils, access to war-economy revenues) are explicit; groups maintain separation from any single state, efficiently serving or fighting across borders; and external logistics and cross-border dispersion are enabling factors. The concept illuminates how controlling actors exploit ethnic solidarity, economic incentives and state fragmentation to operate across multiple political contexts.

By contrast with classical mercenarism—i.e. private military/security companies, typically assessed under the narrow six-part mercenary test in Additional Protocol I, Article 47 (which contractors seldom meet)—ethnic/tribal mercenarism centres on identity-based recruitment, explicit material inducements, and sponsorship/cross-border ties rather than corporate contracting alone. It also differs from rebel governance, which presumes territorial administration of civilians (taxation, justice, services), whereas interest-driven actors may fight for pay without governing territory.

Unlike warlords, who focus on personal control over local political economies and land, ethnic mercenarism relies on cross-border ethnic lines and external logistics, with looser ties to any single locality. Finally, unlike ideology-driven insurgency, where mobilisation rests on doctrine first, ethnic mercenarism fuses identity and materiality.

Thus, the term broadens the civil-war and rebel-governance literature—often centred on rebels who hold territory and govern. While the RSF does not govern in the conventional sense, it provides security services, economic rewards, and a thin political identity—often more effectively than the state. This model blends elements of state-building, rebel entrepreneurship, and identity-based recruitment.

The RSF mobilises fighters not only through ideology or nationalism, but by turning conflict into a sustainable livelihood—akin to armed operations in Chad, where many youths view war not as a disruption of the economy and livelihoods but as an income-generating occupation.

To be continued…

Shortlink: https://sudanhorizon.com/?p=8266