Sudanese Memory: A Reading of 168 Years of Sudanese History Through the Lens of Conspiracy Theory

By: Mohamed El-Sheikh Hussein

History books generally agree that modern Sudan, within its current borders, emerged following the conquest of the country by the forces of Muhammad Ali Pasha in 1821. Some historical texts also assert that modernisation did not reach the Sudanese people until after that invasion—a point that could lead to lengthy debate.

However, Professor Jamal El-Sharif offers a new interpretation of the events that shaped Sudan from 1840 to 2008 in his substantial 1,070-page book titled “The Political Struggle over Sudan 1840–2008”. He does so through the lens of conspiracy theory.

Two Historical Approaches to the Sudanese Question

The “Sudanese question,” in terms of scholarly attention and historical framing, falls into two broad approaches:

The Traditional Textbook Narrative

This approach tends to simplify events, often with a selective focus on heroic moments, elevating their historical value with slogans like: “They braved death for our sake; for this day, they laboured.”

The Colonial Necessity Approach

Here, history was written as a colonial tool to aid the occupiers in governing the country—less a national endeavour and more the work of victors documenting events as they preferred.

Neither of these approaches, however, offers a genuinely critical or comprehensive understanding of Sudan’s historical complexities or the dilemmas such understanding poses.

A Conspiratorial Interpretation

From the outset, El-Sharif makes clear that he adopts conspiracy theory as his framework for interpreting Sudan’s history over these 168 years. He supports his argument with a large number of references—232 Arabic and foreign sources—aiming to highlight the historical collusion of various pressure groups and foreign powers against Sudan.

Impressively, this extensive academic work was completed entirely at his own expense. El-Sharif reportedly spent around 30,000 Sudanese pounds (roughly USD 15,000) of his personal savings to acquire many of these sources from their original repositories.

While this dedication is commendable, it raises important questions. Primarily, does interpreting history through conspiracy theory remain valid in the post-Cold War world? Such a lens may, after all, negate the real struggles of national liberation movements.

Even assuming good intentions, the conspiracy theory model risks portraying national resistance efforts as mere reactions to colonial manipulation, thereby undermining the human dimension of historical struggle.

Substantial Evidence and Historical Staging

El-Sharif backs his views with a wealth of examples. His main thesis: “What the National Salvation Government faces today is merely a continuation of a long-standing strategic conflict.”

He ends the book by probing whether Sudan can be rescued from the trajectory imposed by these foreign conspiracies—past, present, and future.

The author begins his analysis in 1840—a choice that traditional historians may challenge. El-Sharif sees Muhammad Ali Pasha’s 1839 visit to Sudan as the beginning of a political unification with Egypt. He then delves into protests by European powers against Egyptian presence in Sudan, labelling this phase (1840–1879) as “The First Era of Foreign Intervention in Sudan.”

One criticism of this period is the lack of focus on Muhammad Ali’s original motives—namely, his imperial dreams and quest for men and gold. Sudan’s conquest coincided with his campaigns in the Hejaz and Syria, suggesting a broader imperial ambition rather than a focus on Sudan itself.

Still, what distinguishes El-Sharif’s work is his meticulous attention to diplomatic correspondence and foreign involvement, particularly between 1869 and 1879, a period he labels “European Assistance in Governing Sudan.” He then explores the years 1880–1885 as the “Rise of Pressure Groups and the Attempt to Occupy Sudan,” followed by 1885–1898 as “The International Rivalry Play in Fashoda.”

Building the Conspiracy Case

Notably, nearly 42% of the book (454 pages) is devoted to building a theoretical foundation for viewing Sudanese history through a conspiratorial lens. He suggests a continuous strategic conflict aimed at Sudan.

An initial critique: the book overlooks the population movements during the Mahdist Revolution, particularly the west-to-central migration that led to the emergence of Omdurman as a city of cultural fusion between western and northern Sudanese. The late scholar Mohamed Abu Al-Qasim Hajj Hamad thoroughly examined this in his book “Sudan: The Historical Dilemma and Future Prospects”, arguing that the movement mirrored broader migration toward Egyptian cultural centres. El-Sharif missed an opportunity by not incorporating this perspective.

When covering the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium (1898–1956), El-Sharif argues it marked the rise of pressure groups working against British policies. However, this conclusion appears flawed, especially when he cites Britain’s minimal investment in Sudan as evidence. In truth, this was a hallmark of British colonialism globally: minimal spending, low development, and a frugal approach to infrastructure.

A key omission in El-Sharif’s reference list is Dr. Gaafar Mohamed Ali Bakhit’s authoritative work “The Evolution of Governance in Sudan”, which provides a nuanced look at British administrative policies.

A Persistent Conspiratorial Lens

In the 432-page section covering the pre-independence period, El-Sharif continues interpreting Sudanese history through conspiracy theory. While such a method offers one perspective, it can become a limiting filter.

Nonetheless, one must acknowledge that colonial rule in Sudan was based on the Anglo-Egyptian Agreement, which only nominally gave Egypt sovereignty. Britain practised a divide-and-rule strategy and governed with minimal investment, hardly a targeted conspiracy against Sudan specifically.

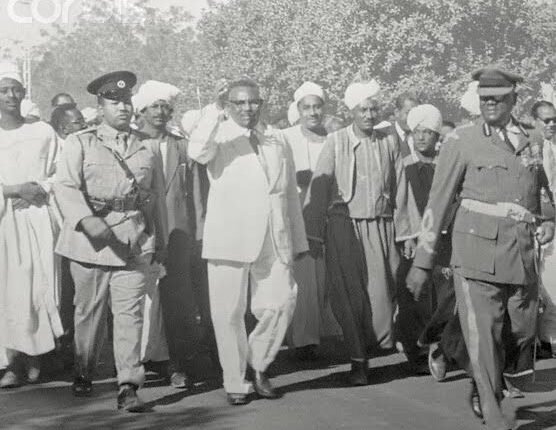

It’s also worth noting that the author gives insufficient attention to President Ismail Al-Azhari’s shift from supporting union with Egypt to advocating for Sudan’s independence. The late scholar Abdullah Al-Tayeb addressed this in his book “Bag of Memories”, offering valuable insights in defence of Al-Azhari.

The Final Chapter: Modern Political Conflict

In the final section of the book—titled “Trends in Political Conflict After Independence 1956–2008″—El-Sharif suggests many events and phenomena are part of a grand conspiracy, made increasingly plausible by the rise of sophisticated intelligence services and think tanks that blur the line between organic and engineered events.

He posits that modern “coincidences” are often deliberate outcomes designed by powerful forces to serve their own agendas. He concludes:

“The political developments in Sudan between 1840 and 2008 were planned and managed by what we now call pressure groups or lobbies.”

This raises the need for a more critical historical understanding. For instance, Hashem Al-Atta’s 1971 coup is not detailed in the book, even though Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, in “A New Look at History”, describes how the execution of Shafei Ahmed El-Sheikh was one of the ten reasons behind the Soviet-Arab fallout at the time.

Still, El-Sharif does not fabricate connections or manipulate facts to serve his theory. Instead, his conclusions, though controversial, are drawn from documented events.

The author ultimately believes that Sudan is one of the main targets of global division strategies, but warns that these threats are only dangerous if the internal front is weak. In contrast, national unity can render such conspiracies powerless.

A Final Word

Following 9/11, the world has indeed entered a Pax Americana era, reminiscent of the Roman Empire’s centuries-long hegemony. We now live in a time where mental supremacy rules, and scientific advancement enable the powerful to dominate and exploit with ease.

To avoid becoming mere spectators in a game run by others, Sudan must harness its intellectual strengths and pursue national unity and a shared vision.

While it’s tempting to embrace a purely conspiratorial view, the course of history teaches us to engage with complexity—to understand the other, their mindset, temperament, and humanity.

The truth remains: life is a relentless struggle with no room for the weak—particularly those who lack insight, experience, or vision.

In conclusion, it is journalistically uplifting to review such a monumental historical work, especially one completed by a fellow journalist through personal effort. Professor Jamal El-Sharif even resigned from a prestigious job and used his retirement savings to gather rare sources and write this book.

That alone is an effort worthy of praise and deep respect.

Shortlink: https://sudanhorizon.com/?p=6172