Commenting on the UAE’s Decisions Towards Sudan… The truth is Revealed and intentions exposed

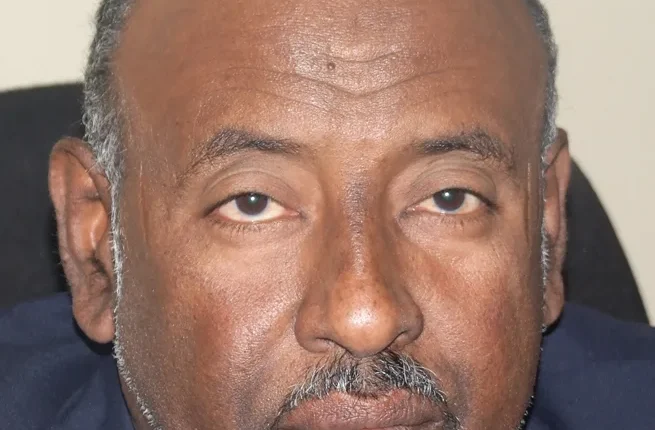

Prof. Ahmed Magzoub Ahmed

Everyone has followed the hasty decisions taken by the United Arab Emirates to halt air and sea transport to and from Sudan, thinking that by doing so, it has strangled the Sudanese economy. It has forgotten, however, that Sudan has a long history of enduring economic blockades and sanctions, stretching from 1983 until today — measures first announced and adopted by the United States of America, then the world’s leading power, at a time when the global financial system was unipolar and centred in the United States. Despite this, Sudan’s path of development and progress continued, as attested by international economic institutions that grew and thrived within that system, especially during the period from 1995 to 2012.

During this time, Sudan became an oil-producing country, exporting various commodities, expanding its infrastructure, boosting its productive capacity, broadening its service institutions, increasing its GDP, and improving average per capita income.

Now, however, the world’s dynamics have changed: a parallel global financial system has begun to emerge, the myth of the unipolar order has broken down, powerful economic blocs have appeared, and an international payment system under China’s sponsorship is being implemented. In this context, the idea of boycotting and economically besieging Sudan no longer carries the same weight it did when the United States first announced it — let alone when such a boycott is declared by its protégé, which counts for very little in the global economy.

It is well known that Sudan produces and exports strategic goods with global demand — such as gold and other minerals, along with a range of agricultural products including gum arabic, sesame, peanuts, sorghum, wheat, cotton, livestock and livestock products, and fishery resources. These vast and varied resources are precisely the reason for the ongoing struggle to monopolise them.

Sudan’s main imports are petroleum derivatives to bridge domestic supply gaps, capital equipment and machinery, some pharmaceuticals, and other luxury goods. It is also well known that the UAE is not a producer of Sudan’s imports, except for a small quantity of oil, which is typically governed by long-term sales contracts that do not place Sudan among the intended buyers. The UAE’s role in this regard has been limited to opening or confirming letters of credit through banking relationships in accordance with standard financial procedures — without any grants or aid involved.

Thus, the UAE’s role does not extend beyond that of a commercial, financial, and logistical intermediary. A country that builds its economy on such services becomes dependent on revenues from these activities — meaning it benefits more from its clients than they do from it.

The mediation role the UAE has played has been chiefly through Sudanese companies based there to take advantage of facilities available to all, or to benefit from transport and handling services through UAE ports — services that are also available at other major commercial hubs worldwide. The UAE is neither a neighbouring state to Sudan nor does it share a border with it, and it derives income from all activities conducted on its soil for Sudan’s benefit.

In today’s competitive global environment for attracting economic, financial, and logistical activities — which generate jobs, boost employment, and increase national income — such services remain readily available in many other countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt. Governments need to review, revitalise, and activate existing trade, financial, and logistical agreements. Some of these frameworks already exist but have weakened due to business being diverted to the UAE. Reversing this only requires resuming operations. For example, Sudan’s trade and logistical cooperation with Saudi Arabia has a long history, and the Kingdom is geographically closer to Sudan, less costly in terms of transport, and more committed to international regulations and standards. Moreover, Saudi Arabia has recently streamlined company registration and business operations, strengthened transparency systems, and risen through sound management to rank as the world’s second — if not first — in financial technology.

Sudan stands to gain much from the UAE’s decisions. The first and most obvious gain will be the return of all gold exports to official channels, as smugglers will no longer find the lawlessness that once protected illicit gold shipments. This means no less than US$1.8 billion will flow back into official channels, with UN estimates placing Sudan’s smuggled gold at between US$1.8 billion and US$3 billion annually. Smugglers will no longer find systems that protect them as they once did.

This is also an opportunity to complete the gold production chain by installing a refinery — a move that will generate substantial revenues that were previously lost under conditions perpetuated by vested interests.

Urgent action by the relevant government bodies to stimulate and activate commercial, financial, and logistical ties between the private sector and the banking system in alternative countries is the first step. The government must adopt a policy of diversifying economic and financial hubs across multiple nations, making it a guiding principle in developing international relations. This is particularly true for countries like Turkey, which has already opened two branches of its leading banks in Sudan and declared its readiness to cooperate in reconstruction efforts — a long-term strategic approach rather than a temporary fix. Sudan should respond to this shift in a way that serves its interests, especially as Turkey has joined the ranks of the world’s major economies.

Strengthening and regulating trade with Egypt is another way to meet the current challenge, though it requires strict, well-designed controls to maximise mutual benefit and curb the smuggling that has expanded during the war, amid insecurity and the state’s weakened control over its borders.

Alongside these urgent measures, Sudan must continue its efforts — begun in 2007 by the Ministry of Finance and National Economy — to join the BRICS group, not as a reaction to the current crisis, but in recognition of the evolving shape of the global economy.

Above all, Sudan needs to reform its foreign trade policies to guide consumption, maximise export revenues, and adopt production strategies that strengthen the productive sector, enabling self-sufficiency and boosting exports. This requires a review of economic, fiscal, and monetary policies to provide the necessary support for this stage.

Shortlink: https://sudanhorizon.com/?p=6941