The Need for Change — and the Central Bank’s Structure

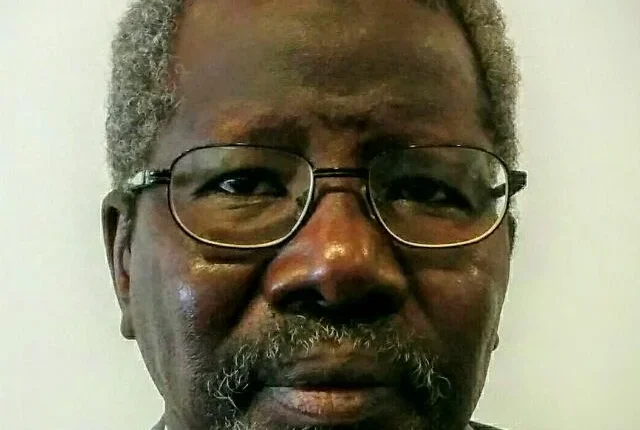

Dr Hassan Isa al-Talib

The chronic problem of the Central Bank of Sudan, which has plagued it since its establishment in 1960, does not lie with the governor or with changing the current office-holders; rather, it lies in the way it takes its decisive monetary and fiscal policy decisions.

The flaw in these practices becomes clear in the rapid turnover at the top. Before Governor Mr Burai, there was Hussein Gengoul. Before them the late Abdul Rahman Hassan, and yet the pound continues to collapse and reel against the dollar and other major currencies. There is no known vision, no roadmap, and no one seems to care. Change always happens in faces only, and nothing else.

The problem at the central bank is not functional but structural. It is determined by the recruitment method and the way governors are selected and appointed. A governor cannot be appointed from a naïve perspective that treats him as a mere employee with long conventional banking experience sufficient to run a twenty-first-century central bank. We must look at how the central bank was established to draw lessons: three experts were brought from the U.S. Federal Reserve in 1957 and contributed to drafting the bank’s law.

Where are we in relation to that day, and what is the level of technical cooperation in attracting global expertise — and who are people like Professor Jeffrey Sachs to us?

Globally, central bank governors are appointed via competition, selecting the highest and best-qualified candidates, and they enjoy full independence from the executive branch. This is the practice in the UK, Canada, India, Nigeria and South Africa. What prevents the Sudanese from doing the same?

The governor of the central bank is not an ordinary civil-service official governed by routine public-service rules; he is an independent authority in carrying out the mandate of managing money and finance, with impacts on the country’s economic growth, unemployment and employment rates, investment and inflation. Central bank governors work within teams of experts, researchers and specialists across all relevant fields.

It is clear that the central bank lacks up-to-date oversight and follow-through, as evidenced by the sustained failure to find solutions outside the repeated bureaucratic box. Therefore there must be an advisory body of experts and specialists to offer development visions and proposals, to keep pace with developments in the rapidly evolving global financial and monetary system — especially in areas such as digital currencies, gold reserves and foreign currency holdings, money supply ratios, and bilateral currency agreements with countries that have significant commercial, financial and investment influence on Sudan.

This does not happen at the Central Bank of Sudan, and no one cares, because the antiquated civil-service bureaucratic mentality that has governed the bank since the last century still dominates its decisions. The question is: what prevents the employment of national and international experts to benefit from their opinions and experience?

As long as things stand as they are, no real change will occur unless the central bank is restructured with the deliberate aim of creating a scientific vision based on operational specialisation, up-to-date knowledge and follow-up, which is then translated into a roadmap, plans and programmes. These should be widely discussed among experts and specialists, followed by a trusted body for evaluation, reform and accountability.

One cannot repeat the same experiment dozens of times with the same inputs and expect different results. This is professional stupidity, managerial folly, a waste of time and an unnecessary squandering of money and effort.

The structural framework must be replaced, and current inputs must be changed to obtain different outcomes. God does not change the condition of a people until they change what is within themselves.

Shortlink: https://sudanhorizon.com/?p=8150