The US Between the Hammer of External Influence and the Anvil of Domestic Affairs

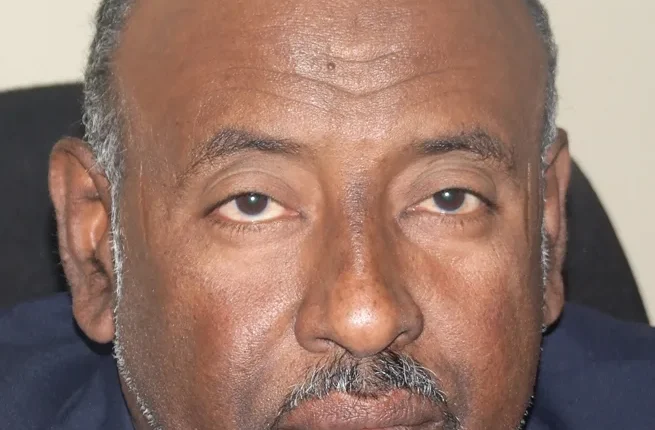

Professor Ahmed Majzoub Ahmed

Is the situation currently facing the United States of America—and its repercussions for the dollar—comparable to what the pound sterling faced in Britain after the Second World War? Or is the process unfolding at a faster pace than that experienced by sterling?

Numerous indicators are pointing to the multiplicity and diversity of economic challenges confronting the US economy, suggesting that the era in which the United States unilaterally led and dominated the world based on its political and economic power—a condition that prevailed in recent decades—is coming to an end. This is not a prediction, but rather a reading of both internal and external indicators.

Those interested in global affairs will no doubt have followed media reports in recent weeks about the adoption of a new US strategy, the essence of which is the reordering of foreign policy priorities: focusing on major powers such as China and Russia, assigning lower priority to the Middle East, increasing concentration on Asia and, subsequently, the Pacific, strengthening US deterrence in the western region and defensive perimeters, linking national security with economic policy, adopting a pragmatic approach to alliances, maintaining security support for Israel to fulfil the role assigned to it in the Middle East, reducing traditional military commitments, and concentrating efforts on domestic US issues.

It is well known that the discussion and adoption of any new strategy does not occur in a vacuum, but is built upon an analysis of the current situation. Review and subsequent change undoubtedly signal that the existing strategy is no longer suited to evolving local and global economic, political, and social variables—an indication that new factors have emerged and will shape what follows.

Reality shows that the United States is no longer the same image it once constructed for itself and persuaded the world to accept. The erosion of this position has prompted some states and political and economic groupings to seek parallel alternative paths, so as not to place all their eggs in one basket.

On the economic front, the United States has for years been grappling with economic challenges that have affected its domestic policies and external posture. The budget deficit reached its peak in 2020, hitting 14.9 per cent of GDP due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It declined to 5.6 per cent in 2021 and is expected to end 2025 at 6.4 per cent—high figures by standards of fiscal sustainability. When measured against annual budgets, the deficit may exceed 25 per cent, underscoring the fragility of the state’s financial position.

On the other side, domestic debt surpassed 120 per cent of GDP in 2020, remained at similar levels thereafter, and is expected to stabilise at this rate until the end of 2025. Against this backdrop, President Trump’s measures in the first quarter of 2025 aimed to review tariff structures—particularly those targeting the People’s Republic of China, America’s largest economic partner. These measures dealt a fatal blow to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), which the United States had long sponsored and supported. Yet they failed to achieve their intended objective of improving the budgetary position, leaving implementation of the President’s reform package uneven and unstable.

These measures coincided with the growth and expansion of the BRICS bloc, which represents a genuine threat to global US influence and to domestic economic stability. The bloc’s activities have gone beyond economic cooperation among its founding members to embrace calls for establishing an alternative global order. It has announced the implementation of an international payments system parallel to the dollar-based global system, under which the United States has acted as the world’s financial policeman monitoring global capital flows.

This shift marks the beginning of a retreat of the dollar as a global currency. Matters were further complicated by the acceptance by a number of major Middle Eastern oil producers of settling oil and petroleum product trade in currencies other than the dollar. These developments signal the waning of the petrodollar, which dominated global oil trade in previous decades. This will undoubtedly weaken US economic influence, depriving America of its ability to appropriate the world’s wealth through the dollar—printed by US currency presses and backed by little more than American protection.

When this is read alongside the impact of rising domestic debt and budget deficits on internal stability, and the beginning of a decline in holdings by major purchasers of US Treasury bonds—China’s share, for example, has fallen by around 25 per cent, from one trillion dollars to approximately 750 billion dollars compared with 2024, while European holdings have largely remained stable—it points to a waning appetite for these instruments. Notably, the United States has been forced to raise bond yields to around 10 per cent annually, increasing debt servicing costs and further pressuring an already deficit-ridden federal budget.

Should the dollar’s retreat as a global currency continue, alongside higher bond yields, the fiscal deficit will worsen as external debt servicing costs rise. Any decline in global demand for these bonds would compel the US Treasury to market them domestically, increasing reliance on internal markets. This would crowd out private-sector access to domestic financing and mark the onset of economic distortions—chief among them rising inflation.

All of the above point to a continued decline in the dollar’s status as a global currency and the expansion of alternative currencies, such as the Chinese yuan, the Russian rouble, or any currency agreed upon by BRICS members for settling intra-bloc trade.

These indicators, together with statements by many American economists and former officials of international economic institutions asserting that the US economy is in sustained decline, and that emerging economies and new economic groupings will lead the world and end the era of US dollar dominance, reinforce the conclusion that America’s economic role and global influence will continue to diminish. Among the most telling remarks on China’s economic rise is one attributed to the US Secretary of the Treasury, who stated that China’s global trade surplus constitutes a threat to the global economy and that he had asked China’s friends to urge it to reduce this surplus by increasing consumption—an admission reflecting the scale of US alarm at China’s economic growth.

On the political front, many values of freedom and justice have eroded. A clear example is President Trump’s remarks about US Congresswoman Ilhan Omar, of Somali origin. Add to this the confrontations faced by some migrants, the mobilisation against both new and long-standing immigrants—many of whom hold US citizenship—and broader signs of political and social retrenchment and insularity, the sheer number of which would warrant a separate article.

Finally, the question remains: will politicians in the developing world—who rush towards America—take heed that they are chasing a mirage and clinging to a spider’s thread?

With my regards.

Shortlink: https://sudanhorizon.com/?p=10104